Introduction

Is Iran secretly a nuclear-armed power? The mere possibility raises the stakes for global security. For years, Tehran’s nuclear ambitions have been a flashpoint in international diplomacy – and a source of deep anxiety. If Iran already has a nuclear weapon, the strategic balance of the Middle East would be upended overnight, potentially triggering crises from Tel Aviv to Washington. Officially, Iran insists its nuclear program is peaceful, and most experts say Tehran has not yet built a bomb. But whispers of hidden warheads and covert experiments persist. In this deep dive, we examine what mainstream authorities believe, and why some evidence – from dissident revelations to suspicious nuclear maneuverings – has led others to wonder if Iran might have crossed the nuclear threshold in secret.

Mainstream Expert Consensus

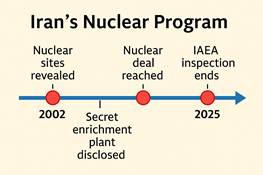

According to international watchdogs and intelligence agencies, Iran does not currently possess an actual nuclear weapon. The prevailing view, supported by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and U.S. intelligence assessments, is that while Iran’s nuclear program has advanced, it has stopped short of constructing a bomb. In early 2025 testimony, U.S. Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard reaffirmed the consensus: “The [Intelligence Community] continues to assess that Iran is not building a nuclear weapon and Supreme Leader Khamenei has not authorized the nuclear weapons program that he suspended in 2003.”{1] This echoes a consistent judgment held since 2007 – that Iran halted its organized weapons program in 2003 and, despite expanding enrichment capacity, has not decided to resume work on an actual warhead.

The IAEA, which monitors Iran’s declared nuclear facilities, has not reported evidence of an assembled nuclear device. Iran is often described as a “nuclear threshold state” – it has mastered the technology to enrich uranium to high levels and researched weaponization in the past, but is not known to have a functioning nuclear bomb[2]. In December 2023, a report by Iran Watch summarized that “Although it is not known to possess nuclear weapons, [Iran] possesses the technologies needed to build nuclear warheads”[3]. In other words, Iran has the know-how and fissile material stockpiles (notably a growing stock of highly enriched uranium) that put it uncomfortably close to a bomb’s worth of material, yet crossing that final line – assembling a deliverable nuclear warhead – is something the regime is widely thought not to have done at this point.

International inspectors continue to keep a close eye on Iran’s known nuclear sites under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) safeguards. Enrichment activities at facilities like Natanz and Fordow are verified (with Iran even allowing additional monitoring under the now-frayed 2015 Iran nuclear deal). The IAEA has detected uranium enriched just shy of weapons-grade at Fordow (83.7% purity in one instance), raising alarms, but still no proof of a weapon or the diversion of fissile material to a secret bomb project. U.S. and European intelligence services likewise say they have not seen clear signs that Iran has built or acquired a nuclear warhead as of today. In fact, American officials – even while warning about Iran’s nuclear progress – often emphasize that Iran could make a bomb in relatively short order if it chose to, but that they believe no bomb has been built yet and no such decision to build one has been made. This mainstream consensus underpins current policy: to prevent Iran from ever obtaining a nuclear weapon, on the assumption it has none so far.

Evidence Suggesting Iran May Already Possess a Nuclear Weapon

Despite the official consensus, various claims and circumstantial evidence have led some observers to suspect Iran might already have developed or obtained a nuclear weapon on the sly. It’s a controversial minority view – and many of these claims are unverified – but they are intriguing enough to examine. Below, we explore the main pieces of evidence and assertions fueling this speculation, and assess whether they hold water:

- Dissident Revelations of Secret Nuclear Sites: Exiled Iranian opposition groups, most notably the National Council of Resistance of Iran (NCRI), have a track record of exposing Tehran’s clandestine nuclear activities. The NCRI (linked to the MEK dissident group) revealed Iran’s secret uranium facilities at Natanz and Arak back in 2002, sparking the first international inspections. In late 2005, the NCRI also disclosed an underground enrichment site near Qom – information that foreshadowed the 2009 public exposure of the Fordow plant by Western governments[4]. Such past accuracy lends credibility when these groups make new claims. And indeed, the NCRI today alleges that Iran already has a nuclear weapons program underway in secret, despite the regime’s denials. In February 2025, the NCRI released intelligence about a covert facility codenamed “Rainbow” which is allegedly dedicated to developing nuclear warheads[5]. According to the NCRI’s report, this sprawling site in Semnan province – disguised as a chemical plant – is working on extracting tritium and other bomb components needed for boosted atomic warheads and even hydrogen bombs[6]. Iranian dissidents claim that experts from Iran’s secretive SPND organization (in charge of weaponization research) have been reassigned to this site to advance a nuclear weapons project[7]. Tehran, for its part, vehemently dismisses these reports as “fabrications,” but the detailed allegations raise the question: could Iran have a parallel, undeclared weapons effort? The NCRI asserts that yes, and even suggests Iran may have already built at least a rudimentary nuclear explosive device. While no independent verification of the “Rainbow” site exists, the mere existence of undeclared nuclear facilities – if true – would indicate Iran might be further along the bomb path than generally thought.

- Past Accuracy of Opposition Intel – Fordow and Others: It’s worth underscoring how groups like the NCRI earned their reputation. In September 2009, the world learned of Iran’s clandestine Fordow uranium enrichment facility – a heavily fortified bunker under a mountain near Qom. Western intelligence had suspected it for months, but interestingly, the NCRI had already hinted at Fordow’s existence years prior. In a 2005 press conference, NCRI officials detailed underground nuclear sites under construction near Qom and Tehran; four years later, the U.S., UK, and France confirmed Fordow publicly, only after Iran was forced to acknowledge it to the IAEA[8]. This and other revelations (like the exposure of Iran’s “Amad” nuclear weapons research documents, or secret sites at Parchin) show that Iranian insiders have leaked valuable information in the past. Therefore, when the same opposition sources now claim Iran may already possess a nuclear weapon or at least a warhead design, some analysts take notice. Skeptics caution that the NCRI/MEK have their own agenda and cannot provide hard proof to back such dramatic claims. Still, their consistent record of uncovering nuclear secrets (often later verified by inspectors) means these assertions, however sensational, cannot be entirely dismissed without investigation.

- Iran Allegedly Moving Nuclear Material Ahead of Attacks: Another piece of circumstantial evidence comes from recent military confrontations. In mid-2025, amid a major Israel-Iran conflict, Iranian nuclear facilities were targeted by airstrikes. Yet reports emerged that Iran had preemptively removed or secured nuclear material before the bombs fell – almost as if they anticipated the strikes and wanted to preserve their most sensitive nuclear assets. According to Israeli officials who briefed The New York Times, the fortified Fordow enrichment site – struck by bunker-buster bombs – was not completely destroyed, in part because the Iranians **“had moved nuclear materials like uranium out of the site before the bombing.”*[9] U.S. military sources corroborated that account, noting that even multiple heavy bombs could not entirely level Fordow (built deep under rock) and that much of its nuclear stockpile was kept safe elsewhere[10]. An adviser to Iran’s parliament speaker later openly claimed that “the site [Fordow] has long been evacuated” in anticipation of an attack[11]. In other words, Iran itself hinted that it had relocated key nuclear infrastructure from Fordow ahead of the strikes, and thus “no irreversible damage” was done[12]. Such actions suggest a high degree of advance planning to protect nuclear material. Critics wonder: why would Iran quietly empty an enrichment plant before an attack unless something very valuable – perhaps weaponizable uranium or equipment – was at stake? One interpretation is that Iran may have been safeguarding ingredients for a bomb, moving them to undisclosed locations so that even if known sites are hit, a covert weapons program could survive. It’s not direct evidence of a finished weapon, but it does indicate Iran wanted to ensure the survival of something important to its nuclear capabilities.

- Iranian Representatives at North Korean Nuclear Tests: Iran’s long-standing collaboration with North Korea is another factor that feeds speculation. If Iran has a bomb, some argue, it may have benefited from Pyongyang’s nuclear advances – either through shared data or even participating in North Korean nuclear tests. Indeed, there have been multiple reports over the years of Iranian scientists or military officers observing North Korea’s nuclear detonations. For example, Japan’s Kyodo News (citing a Western diplomatic source) reported that “Iranian scientists were likely present” when North Korea conducted its third underground nuclear test in February 2013[13]. Allegedly, Iran paid North Korea millions of dollars for the privilege of sending observers to this test[14]. Around the same time, The Sunday Times and Israeli intelligence sources claimed that Mohsen Fakhrizadeh-Mahabadi – regarded by Western agencies as the head of Iran’s nuclear weapons program – traveled to North Korea to be present at that nuclear detonation[15]. (Fakhrizadeh was an Iranian nuclear scientist so important that Israel assassinated him in 2020.) Additionally, The Jerusalem Post reported that Iranian nuclear experts were “present, according to several indicators,” at Pyongyang’s test site during that 2013 test[16]. If these accounts are accurate, Iran would have gained firsthand knowledge of actual nuclear bomb performance – data invaluable for designing its own devices. Furthermore, North Korea and Iran have openly cooperated on long-range missiles for decades, and there’s strong suspicion they have exchanged nuclear weapons know-how as well[17]. The presence of Iranian personnel at foreign nuclear tests suggests a literal crossing of paths between Iran’s program and an existing nuclear weapons state. Some analysts even posit that North Korea might have conducted proxy nuclear tests on behalf of Iran, allowing the Iranians to validate a design without detonating a device on Iranian soil. All of this bolsters the possibility that Iran could possess at least a tested design or prototype obtained through North Korean assistance – if not an actual assembled bomb.

- Claims by Former Officials and Analysts: Beyond the shadowy world of espionage and dissidents, some Western experts have publicly argued that Iran likely already has a bomb or two. These claims, while controversial, come from figures with past high-level intelligence credentials. For instance, in 2016 a group of former U.S. national security officials – including ex-CIA Director R. James Woolsey and a former White House science adviser – warned that “Iran probably already has nuclear weapons.”[18] They pointed out that Iran mastered key bomb-making steps (like building detonators and designing warhead blueprints) well over a decade ago[19]. Given that Iran was “already a threshold nuclear-missile state” by the mid-2000s, they found it “implausible” that Tehran would then voluntarily freeze its weapons program for years just for the sake of the 2015 nuclear deal[20]. These experts suspect Iran continued a clandestine weapons effort and likely “has nuclear warheads for the Shahab-III medium-range missile” ready to go[21]. Similarly, Reza Kahlili – a pseudonym for a former Iranian Revolutionary Guard officer who worked as a CIA spy – has claimed since the early 2010s that Iran obtained several nuclear warheads from the ex-Soviet stockpile and has them hidden. (Kahlili even offered to provide photographs of these alleged weapons to U.S. intelligence, though his claims were never verified[22].) While the mainstream view discounts such assertions, the fact that veteran analysts and defectors are willing to stake their reputations on Iran already having the bomb is notable. They argue that the West may be committing a dangerous intelligence failure by assuming Iran is still bomb-free[23] – recalling how the U.S. underestimated North Korea’s rapid nuclear progress in the past. These voices urge that prudent strategy must consider that Iran could have one or several nuclear weapons in secret, even if no test has occurred.

In sum, there is no smoking-gun proof that Iran possesses a working nuclear weapon at this moment – no seismic shock of a test, no satellite image of a warhead – and official bodies like the IAEA and CIA maintain that Iran has not made a bomb. However, the circumstantial evidence above keeps alive a lingering doubt. Iran’s nuclear program has involved much secrecy and deception historically, so analysts cannot completely rule out that something was accomplished behind the curtain. From dissident allegations of covert sites and warhead development, to suspicious moves and foreign collaborations, these clues collectively suggest it is possible (though unproven) that Iran might have produced at least a crude nuclear device already.

Why Iran Might Not Have Used or Revealed a Nuclear Weapon Yet

Suppose, for the sake of argument, that Iran does already have one or a few nuclear weapons. A big question then arises: Why haven’t they announced it or tested one? What would Iran gain by hiding a bomb, when nuclear powers typically use overt possession as a deterrent? There are several plausible reasons – strategic, technical, and political – why Tehran might choose to keep a nuclear weapon secret (and unused) for now:

- They only have a small number (or a single prototype): If Iran’s hypothetical nuclear arsenal is very limited – say only one or two devices – the leadership may be reluctant to “spend” one on a test or reveal their hand. A lone nuclear weapon would be more useful as an ace up the sleeve than as a publicly declared capability. By keeping it under wraps, Iran could avoid triggering international retaliation while still retaining the option to use it in an absolute emergency. In contrast, using or testing that one bomb would immediately strip them of the element of surprise and invite overwhelming military and diplomatic backlash. Historically, nations with minimal arsenals have been cautious: for example, when South Africa secretly built a handful of bombs in the 1980s, it never tested or brandished them, instead waiting for a grave threat that never came. Iran may similarly calculate that a hidden “insurance” device is only useful as long as it stays hidden. Essentially, if you have only one arrow in your quiver, you don’t fire it unless you absolutely must.

- The device might be untested or not yet deliverable: There’s a difference between possessing a crude nuclear explosive and having a reliable, weaponized nuclear warhead. It’s possible Iran could have assembled a basic nuclear device (for instance, as a proof-of-concept) that is too bulky or fragile to mount on a missile. Such a prototype might not be suitable for military use without further refinement. Iran wouldn’t want to flaunt a bomb that it isn’t confident can actually detonate as intended. Conducting a nuclear test would be one way to prove the design works – but testing would blow their cover and invite sanctions or attack. So if Iran has a device that hasn’t been tested, they face a conundrum: using it or testing it risks failure or international wrath, while keeping it secret preserves the option to improve it quietly. They may be content to hold off on any demonstration until they can build smaller, fully deployable warheads (and perhaps accumulate a few of them for a credible arsenal). In this scenario, Iran’s bomb is a prototype still in the shadows, awaiting the right moment (or technological breakthrough) to be revealed.

- Strategic Ambiguity – following the Israel model: Iran may be intentionally emulating the strategy of nuclear opacity practiced by Israel. Israel is widely known to possess nuclear weapons (estimated ~90 warheads or more), yet it has never officially confirmed this and has never conducted an overt nuclear test[24]. This policy of “strategic ambiguity” – neither confirm nor deny – has allowed Israel to reap the deterrent effect of a nuclear arsenal while avoiding some of the diplomatic consequences. Iran could see value in a similar posture. By not announcing a bomb, Iran avoids crossing a red line that could trigger preemptive attacks or a regional arms race. At the same time, the mere possibility that Iran might have a nuke can inject caution into its adversaries’ calculations. As one analysis noted, maintaining a threshold capability without open weaponization “generates enough uncertainty to make Western powers cautious… It creates a degree of deterrence without escalation.”[25] In fact, Tehran has already benefited from this to an extent – its aggressive uranium enrichment and nuclear know-how have altered the regional balance even without an actual bomb in hand[26]. If Iran secretly has developed a weapon, choosing ambiguity lets it enjoy a deterrent shadow: enemies may think twice (“What if Iran does have a nuke?”) but Iran doesn’t have to deal with the fallout of outright breaching the nuclear taboo. In short, keeping any nuclear weapon secret could be Tehran’s way of deterring attack à la Israel – creating fear and uncertainty, but avoiding the provocations of open deployment.

- Fear of a Preemptive Strike or Global Backlash: Were Iran to suddenly test a nuclear bomb or declare itself nuclear-armed, it could provoke immediate and severe consequences. Israeli and U.S. leaders have long warned they would not tolerate a nuclear-armed Iran. An open admission by Iran could be the spark for military action to destroy its remaining nuclear infrastructure before it can build more bombs. Iran’s leaders are keenly aware of what happened to other regimes that pursued WMDs: for example, Saddam Hussein’s Iraq (suspected of nuclear ambitions) was invaded, and Muammar Gaddafi, who gave up Libya’s nascent nuclear program, was overthrown years after doing so. If Iran announced a nuke, it might unify much of the world in isolating Tehran completely – even countries like Russia or China would face pressure to join punishing sanctions against an Iran that broke the NPT rules so brazenly. By staying officially non-nuclear, Iran avoids crossing that threshold of opprobrium. This calculation could be a powerful motivator: do not give the hawks a clear justification to attack. As long as Iran’s status is ambiguous, there is hesitancy – a small chance to maintain business as usual. Once it’s confirmed to have a bomb, that restraint could evaporate, and Iran would be in the crosshairs of a potential multi-national military campaign. Thus, if Tehran does have a secret weapon, hiding it is a form of self-preservation.

- Preserving Political and Religious Legitimacy: Iran’s regime has consistently maintained that it is not seeking nuclear weapons, both for diplomatic reasons and ideological ones. The Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei even issued a fatwa (religious edict) declaring nuclear weapons forbidden by Islam[27]. Admitting to possessing a nuke would flatly contradict this edict and undermine the regime’s credibility at home and abroad. It would amount to confessing that years of assurances about “peaceful purposes only” were lies. Such a move could alienate Iran’s few remaining international partners and perhaps sow doubt among some of its domestic supporters who believed the regime’s statements. By contrast, sticking to the line that “we have no nuclear weapons and don’t want any” – even if disingenuous – allows Iran to dodge that self-inflicted legitimacy crisis. In the Iranian leadership’s eyes, the ambiguity or denial approach keeps the moral high ground (at least in public rhetoric), portraying Iran as a victim of unfounded Western accusations. Only under extreme circumstances might they reverse that stance. One line of thinking even suggests Iran would only openly brandish a secret nuke if doing so could be framed as a defensive necessity (for example, if the regime’s survival were at stake due to war). Until then, keeping any nuclear weapon undeclared avoids exposing the regime’s duplicity vis-à-vis its oft-stated religious and legal commitments.

- Waiting for an Optimal Strategic Moment: It could be that Iran is biding its time – holding a nuclear capability in reserve until it can be revealed to maximum strategic advantage. This might mean waiting until Iran has built up enough weapons (and long-range missiles) to truly deter any retaliation. Or waiting for a geopolitical crisis where unveiling a nuclear weapon could shock adversaries into backing off. Some analysts speculate that Iran might be following North Korea’s playbook in slow motion: develop the arsenal covertly, and only declare/test a weapon when you’re ready to face the world as a nuclear-armed state with a fait accompli. By that point, it would be too late for the international community to prevent Iran’s nuclear status. If Iran indeed already has a bomb, it may be calculating that the benefits of keeping it secret for now outweigh the benefits of brandishing it – until some future tipping point is reached. Essentially, Tehran may be keeping its nuclear card close to the chest, to be played at a time of its choosing (for instance, if an existential war looms or if it achieves a critical mass of weapons).

In combination, these factors explain why, even if Iran does have a nuclear weapon, we haven’t seen it. Secrecy serves Iran’s interests in many ways at this stage. A hidden nuke still acts as a deterrent (if adversaries suspect its existence), yet avoids the grave risks that come with open admission. It fits with Iran’s pattern of ambiguity and gradual escalation. And it aligns with the regime’s desire to avoid uniting the world against it or giving an excuse for an invasion. Of course, all this is predicated on the hypothetical that Iran actually possesses a nuclear weapon – a point which remains unproven. But these are the rationales that often come up in strategic discussions about what Iran’s behavior would be if they had the bomb already.

Conclusion

The safest assessment, and the one shared by most experts, is that Iran does not yet have a nuclear bomb in its arsenal. The International Atomic Energy Agency and U.S. intelligence continue to monitor Iran’s program closely, and as of now they have not identified evidence that a weapon has been built or that enough fissile material has been diverted for one. This mainstream view holds that Iran, while dangerously close to nuclear-weapons capability, remains short of the finish line – in part due to international pressure, inspections, and Iran’s own calculated caution.

However, the absence of proof is not proof of absence. The possibility that Iran may already possess a nuclear weapon cannot be entirely dismissed, given the shroud of secrecy over parts of its program and the history of surprises in nuclear proliferation. We recall that in 2009, Iran was caught hiding a whole enrichment facility at Fordow; in 2018, Israel revealed Iran’s secret nuclear archive, showing past weaponization work that extended further than many realized. Nuclear history is rife with intelligence underestimation – from the Soviet Union’s first bomb in 1949, to China’s in 1964, to the rapid progress of Pakistan and North Korea. In each case, the world was caught off-guard to some degree. It is not impossible that Iran could have managed a similar feat of strategic deception. Tehran’s regime has certainly tried to mask its intentions at every turn, exploiting diplomatic negotiations and ambiguities to buy time for its nuclear advancements[28]. As one group of analysts warned, assuming Iran has no weapons until it loudly tests one could become a grave intelligence failure[29].

What does this mean going forward? It means that while we operate on the assumption that Iran is not yet a nuclear-armed state, prudent policy must stay alert to the slim but serious possibility that Iran has already crossed the nuclear threshold in secret. The stakes of being wrong are enormous – a nuclear Iran would dramatically shift military and political calculations across the Middle East. Therefore, defense planners and diplomats would do well to “factor in” this worst-case scenario, even as they continue efforts to prevent it. Verifying the truth is extraordinarily difficult in a closed society like Iran’s, but vigilance is key.

In the end, the question “Does Iran already have a nuclear weapon?” remains unanswered with certainty. The weight of evidence still suggests “probably not yet.” Yet, as in the game of Schrödinger’s cat, until the box is opened – or in this case, until Iran’s program is fully transparent or a weapon is incontrovertibly revealed – the world must live with a degree of uncertainty. History and logic counsel caution: Iran might not have the Bomb today, but the world cannot be 100% sure. Given the potentially catastrophic implications, it is wise to keep both eyes open – and continue to pressure for inspections, intelligence gathering, and robust preventive measures – precisely because the cost of being blindsided by a hidden nuclear weapon is so high. The consensus may say “no bomb now,” but until Iran’s nuclear file is resolved conclusively, that unsettling question will continue to loom over global security.