Imagine a flash on the horizon and a mushroom cloud rising – a nuclear blast that breaks an almost 80-year taboo. Would Russia ever really pull the trigger? The question of how far Moscow might go with its nuclear weapons has haunted diplomats and citizens alike since the Cold War. Today, Russia possesses the world’s largest atomic arsenal, and its leaders frequently remind the world of this deadly fact. From giant strategic warheads that can level cities to “tactical” nukes meant for the battlefield, Russia’s attitude toward nuclear use has evolved over time – and grown increasingly vocal. Understanding Russia’s nuclear doctrine is key to gauging what might trigger such a nightmarish escalation and how it could unfold. This deep dive explores Russia’s historical and current philosophy on nuclear weapons use, what could push the Kremlin toward the unthinkable, and how any use might dangerously escalate. It’s an eye-opening look at the balance of terror Moscow seeks to maintain, and whether recent threats are bluster or a genuine warning.

Historical Evolution of Russia’s Nuclear Policy

During the Cold War, the Soviet Union and United States adhered to the grim logic of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) – the idea that a nuclear war would annihilate both sides. This created a powerful “nuclear taboo” against actually using the Bomb. In 1985, U.S. President Ronald Reagan and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev even declared that “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought,” cementing the notion that any nuclear exchange would be suicide[1]. The Soviet Union in 1982 went so far as to pledge no first use of nuclear weapons. However, the end of the Cold War and the Soviet collapse brought major shifts in policy.

In the 1990s, Russia’s conventional military power sharply declined, and nuclear weapons assumed a greater role as the ultimate safeguard of Russian security[2]. In 1993, President Boris Yeltsin’s government abandoned the Soviet no-first-use pledge, asserting that Russia could use nuclear weapons even if attacked with purely conventional forces – specifically if Russia were attacked by a non-nuclear state allied with a nuclear power[3]. This was a dramatic change, reflecting Moscow’s insecurity after losing the vast Soviet-era army. By the end of that decade, Russia was openly practicing nuclear scenarios in military exercises. In 1999, facing NATO’s superior conventional capabilities, Russia’s Zapad-1999 war game simulated nuclear-capable missile strikes against NATO targets to stave off defeat[4]. The message was clear: in a dire situation, Russia might escalate to nuclear use to compensate for conventional weakness.

Moscow formalized this stance in its 2000 military doctrine. The doctrine stated that if a war could not be won by conventional means, Russia would resort to nuclear weapons to end the conflict on favorable terms[5]. Scenarios for nuclear first-use included retaliation not only for an enemy nuclear strike but even for a massive conventional attack “in situations critical to the national security” of Russia[6]. In other words, if Russia were losing a major war, it reserved the option to fire the nukes. This concept laid the groundwork for what later became known as “escalate to de-escalate” – using a limited nuclear strike to force the enemy to stand down.

Through the 2000s, as Russia rebuilt some conventional strength, it raised its official nuclear threshold somewhat. The 2010 and 2014 updates to Russia’s doctrine narrowed the conditions for nuclear use to instances when “the very existence of the state is threatened,” replacing the vaguer “critical to national security” phrasing[7]. This was interpreted as a higher bar for first use, implying Russia would fire nukes only if the country’s survival were truly on the line (for example, if Moscow faced a large-scale invasion). This change coincided with improvements in Russia’s non-nuclear forces and new precision weapons, which made it less immediately reliant on nukes[8]. Still, Russia never adopted a no-first-use policy – it consistently kept nuclear arms as a fallback option in any major war.

By 2020, Russia released an official document titled “Basic Principles of State Policy on Nuclear Deterrence,” which for the first time openly listed the main scenarios that could lead Moscow to use nuclear weapons. According to this policy, the Russian President is the ultimate decision-maker on launching nukes[9]. The declared scenarios for nuclear use were as follows[10]:

- Nuclear or WMD Attack – If an adversary uses nuclear or other weapons of mass destruction against Russia or its allies, Russia may respond with nuclear strikes.

- Incoming Missile Attack – If Russia detects the launch of ballistic missiles headed toward its territory or that of its allies, it could launch nuclear weapons on the assumption of an incoming nuclear strike (launch-on-warning).

- Critical Infrastructure Attack – If an enemy attack (even with conventional forces) hits Russian critical military or government sites in a way that cripples Russia’s nuclear response capability, it could trigger a nuclear retaliation.

- Existential Threat – If Russia faces conventional aggression that threatens the very existence of the state, it may use nuclear weapons to repel it.

Notably, this 2020 policy still emphasized that nuclear weapons are a tool of deterrence and last resort. It claimed Russia views nukes only as a defensive measure to be used in “extreme circumstances.” However, it also maintained deliberate ambiguity – for example, it did not explicitly mention Russia’s sizable arsenal of non-strategic (tactical) nuclear weapons[11], even though those are integral to its warfighting plans. This ambiguity – essentially “keep the world guessing” – has long been a feature of Russian nuclear strategy.

Russia’s Current Nuclear Doctrine and Philosophy

Russia’s nuclear doctrine took a sharper turn amid the war in Ukraine. In late 2024, President Vladimir Putin approved amendments that lowered the threshold for nuclear use even further[12]. Under this revamped doctrine, Russia now “reserves the right” to use nuclear weapons not only in the above scenarios but also in response to a major conventional attack on Russia (or its ally Belarus) that creates a critical threat to the nation’s sovereignty or territorial integrity[13]. Previously, Russian doctrine limited such a response to situations where the state’s existence was at stake or in retaliation for WMD attacks[14]. The new language implies that even a non-nuclear attack – for instance, a NATO-backed conventional strike that threatens to overrun Russian defenses – could trigger a Russian nuclear strike[15].

Moscow also extended its official “nuclear umbrella” over Belarus in 2022–2023, deploying Russian tactical nuclear warheads on Belarusian soil and stating that an attack on Belarus would be treated as an attack on Russia[16][17]. This effectively binds Belarus into Russia’s nuclear red lines. Putin and Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu have repeatedly warned that Russia will use “all available means” to defend itself and have cited these new doctrinal terms to dissuade the West from directly intervening in Ukraine[18]. The Kremlin now frames certain Ukrainian strikes – especially those using Western-supplied long-range missiles – as attacks “with the participation of a nuclear state” (i.e. NATO), hinting that such actions inch close to Russia’s nuclear red line[19].

Russia’s current philosophy thus mixes saber-rattling rhetoric with intentional vagueness. By widening the gray zone of what might prompt a nuclear response, Moscow aims to make NATO think twice about any action that could seriously threaten Russian forces or territory[20]. Western analysts note that this ambiguity is deliberate – a form of psychological deterrence. Every time Russian officials hint at nuclear use, it’s meant to inject fear and caution into Western capitals. Indeed, in the first months of the Ukraine war (2022), Putin’s nuclear threats succeeded in shaping some Western decisions (for example, discouraging early NATO intervention or limiting the types of weapons given to Ukraine)[21][22]. However, as the war dragged on, the West grew somewhat desensitized to Moscow’s bluster[23]. This led Putin to escalate his rhetoric and make the 2024 doctrinal changes to reinforce Russia’s deterrent by words on paper[24].

Despite the tougher talk, most experts assess that Russia’s leadership still views nuclear weapons as a last resort – a “break glass in case of emergency” option. The catastrophic consequences of nuclear war have not changed. Even Putin, for all his brinkmanship, routinely states that nuclear use would only be contemplated if Russia’s fundamental security was endangered. Critics argue that Russia’s expanded red lines are largely a bluff to scare the West. As former U.S. ambassador Steven Pifer observes, launching a nuclear strike in response to a limited conventional attack would be “fraught with political and military peril for Russia,” likely alienating even friendly powers like China and India[25]. In short, Russia’s philosophy is to deter by fear – reminding the world it could go nuclear – while hoping it never has to actually cross that Rubicon.

Strategic vs. Tactical Nuclear Weapons – and Russia’s Huge Arsenal

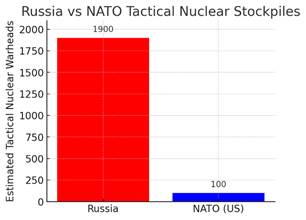

Figure: Estimated number of “tactical” (nonstrategic) nuclear warheads – Russia has roughly 1,000–2,000 such warheads in reserve, vastly more than NATO’s ~100 active tactical warheads.

Russia’s nuclear forces span strategic weapons – high-yield warheads on intercontinental missiles and long-range bombers, meant to destroy entire cities or enemy nuclear forces – and tactical (nonstrategic) weapons, which are lower-yield warheads deployable on shorter-range delivery systems for battlefield use. The label “tactical” can be misleading, however. These smaller bombs are still extraordinarily destructive. Many of Russia’s tactical nukes are “dial-a-yield” designs that can be adjusted from sub-kiloton blasts up to tens of kilotons[26]. For instance, an Iskander-M short-range ballistic missile can carry a warhead of about 5–50 kilotons, and air-dropped bombs for fighter jets might be in the 10–20 kt range[27]. (By comparison, the atomic bomb that obliterated Hiroshima in 1945 was ~15 kilotons.) Some “tactical” warheads in Russia’s arsenal can even reach 100–300 kt[28] – far bigger than Hiroshima – though most are believed to be kept at lower yields for more localized effects. In practical terms, even a “small” 10 kt nuclear explosion could devastate several square miles of a city or battlefield, killing tens of thousands. The nuclear blast, heat, and radiation from any such device would eclipse conventional weapons in destructive power.

Given this potency, what makes a weapon tactical is not its lethality but its intended use. Strategic nukes are meant to annihilate the enemy’s homeland or nuclear forces from afar (e.g. a Russian ICBM striking New York or a U.S. Trident missile striking Moscow). Tactical nukes, by contrast, are meant for more limited aims on the battlefield – such as wiping out a large troop formation, aircraft carrier, or supply hub – without (in theory) triggering full nuclear war. During the Cold War, the Soviet Union amassed thousands of tactical warheads to offset NATO’s conventional military strength in Europe[29]. The idea was that if NATO forces ever overwhelmed Soviet defenses, Moscow could fire a few “smaller” nukes to halt their advance. Today, Russian military writings often speak of using tactical nuclear strikes to “escalate to de-escalate” a conflict[30]. In plain terms, this means escalating a conventional war by using a nuclear weapon in order to de-escalate – i.e. shock the adversary into backing down[31]. The Kremlin envisions, for example, detonating a single low-yield nuclear blast against a critical military target (such as a NATO airbase or carrier strike group) to demonstrate resolve and impose unbearable costs on the enemy[32]. The hope is that NATO, faced with the sudden horror of nuclear warfare, would choose to cease hostilities rather than risk further atomic exchanges[33].

To support this doctrine, Russia has maintained a large and diverse inventory of nonstrategic nuclear weapons. Western intelligence estimates Russia holds roughly 1,000 to 2,000 tactical warheads in storage, ready to be deployed on various delivery systems[34]. These include warheads for short-range ballistic missiles (like the Iskander-M launcher), land-attack cruise missiles that can be launched from naval ships or aircraft, gravity bombs for fighter-bombers, and even nuclear-capable depth charges and anti-air missiles[35][36]. During Soviet times, there were even nuclear artillery shells and landmines. While many older systems were retired, Russia today still fields modern equivalents and “dual-use” weapons that can carry either a nuclear or conventional payload[37]. This arsenal greatly outnumbers NATO’s tactical nuclear forces. The United States, for instance, keeps an estimated 100 B61 nuclear gravity bombs in Europe (at air bases in five NATO countries) for potential use by NATO aircraft[38]. Britain and France have only strategic warheads. In effect, Russia enjoys a 17:1 advantage or greater in tactical nukes in the European theater (as illustrated in the figure above). This disparity has drawn concern, as it might embolden Russian planners to consider limited nuclear use in a regional war, believing NATO’s response options are constrained.

Russia has also taken steps to forward-deploy some tactical nukes for added leverage. In 2023, Putin announced that Russian nuclear warheads would be placed in Belarus, closer to NATO borders[39]. Sure enough, sites in Belarus were prepared to store Iskander missile warheads and aerial bombs[40]. Exercises in 2022–2024 saw Russian units near Europe practicing the procedures for transporting and mating nuclear warheads to their launch systems[41]. These moves aim to shorten the reaction time for Russian nuclear strikes in a conflict – a form of pressure on NATO. It signals that Russia could quickly employ a tactical nuke if it chose, leaving NATO little time to react or interdict. From Moscow’s perspective, this strengthens deterrence by presenting a credible threat.

At the same time, Russian officials insist that nuclear weapons would only be used in extreme cases. The Kremlin often reiterates that nuclear war is something they want to avoid, not fight and win. The troubling question is whether Russia’s leadership might one day judge an extreme case to have arrived – for example, a NATO intervention in Ukraine or a disastrous battlefield loss – and thus feel justified in breaking the nuclear taboo.

What Might Tip Russia into Using Nuclear Weapons?

Under what circumstances would Russia actually cross the line to use a nuclear weapon? Based on its doctrine (and hints from officials), several potential triggers stand out:

- Existential Threat to the State: This is the core scenario where Russia has consistently said it would resort to nukes. If a conventional war put the survival of the Russian state in peril – for instance, if NATO forces were on the verge of overrunning Moscow or toppling the government – Russia might use nuclear weapons to stave off defeat[42]. In Putin’s rhetoric, he often frames major conflicts as threats to Russia’s very existence, implicitly reminding the world that if Russia is pushed to the brink, it could “go nuclear” rather than capitulate[43]. The regime’s survival would trump all other concerns.

- Mass Destruction Attack: If another state launched a nuclear strike on Russia, or attacked Russia (or its treaty allies) with other weapons of mass destruction (biological or chemical weapons), Russia would almost certainly retaliate with nuclear weapons[44]. This falls under classic nuclear deterrence – nukes to respond to nukes (or other WMD). So far, no country has directly attacked Russia with WMD, but the doctrine makes clear that any such attack is a red line.

- Attacks on Critical Infrastructure or Leadership: A decapitation strike against Russian leadership or military command (for example, a strike taking out Russia’s top generals or knocking out its nuclear control systems) could trigger a nuclear response[45]. The logic is that if Russia’s ability to respond is in danger, it may use nukes immediately before it loses that ability. Russia’s early-warning systems detecting an incoming nuclear missile also fit this category – if they believe a nuclear strike is inbound, Russian doctrine allows a pre-emptive nuclear launch (“launch on warning”) to ensure their own missiles aren’t destroyed in silos[46].

- Large-Scale Conventional War Against Russia: This is the more ambiguous trigger that has evolved recently. In the past, it was defined as a conventional attack so severe it threatened Russia’s existence. As of 2024, it has been broadened to a conventional attack causing “critical threat” to sovereignty or territory[47]. Examples might include NATO invading a Russian ally like Belarus, or NATO air forces massively bombing Russian troops. If Russian leaders judge that a conventional conflict (even without WMD) is escalating beyond their control and could lead to Russia’s strategic defeat, they might consider a limited nuclear strike to force a halt. This is essentially the “escalate to de-escalate” scenario. Notably, Putin has pointed to Western involvement in Ukraine (such as providing long-range weapons to attack Crimea or Russian cities) as something that might cross a line. In September 2022, amid battlefield setbacks, Putin warned he would use “all weapons available” to defend Russia’s territorial integrity and said “this is not a bluff”[48][49]. Such statements indicate that if Putin truly believed Russia (or his hold on power) was about to collapse due to a military defeat, the nuclear option would be on the table.

- Demonstration or Warning Shot: Some experts theorize Russia might employ a nuclear detonation as a warning shot – for example, a high-altitude burst or a blast over an unpopulated area – to signal utmost seriousness without mass casualties. This would be intended to show “we mean business” and pressure the enemy to back down. Russian war games have included the idea of a demonstration strike. While not explicitly in doctrine, this could be a political decision in a crisis, especially if Putin wanted to frighten adversaries yet avoid immediate full-scale war. Even a demonstration blast, however, risks uncontrollable escalation.

- Accidents or Miscalculation: Beyond deliberate policy, there’s always the danger of an accident or false alarm. A radar glitch might mistakenly warn of incoming missiles, or a local commander under intense pressure might use a tactical nuke without clear orders. The Cold War had several close calls where technical errors nearly led to launch. Russia’s command-and-control system (including the Cheget nuclear briefcase Putin carries[50]) is supposed to prevent unauthorized launches. But in the fog of war, especially if communications break down, the probability of miscalculation rises. This is a wildcard scenario – not intended by policy, but possible if things spiral out of control.

In summary, Russia might be tipped toward nuclear use if facing military disaster or a threat that Putin deems existential. The war in Ukraine has tested these red lines. For instance, when Western nations floated the idea of helping Ukraine retake Crimea (which Russia claims as its own), Putin hinted at nuclear retaliation by calling Crimea “sacred” and saying he would use all means to defend it. So far, Russia has held off actual nuclear use in Ukraine, likely because none of the triggers (like direct NATO intervention) fully materialized, and the costs still outweigh any gains. But the world watches every twist of that conflict nervously, knowing that if Putin feels cornered enough, the unthinkable could potentially happen.

How Nuclear Use Could Escalate

Any Russian use of a nuclear weapon – even a so-called “limited” tactical strike – carries a grave risk of escalation beyond anyone’s control. Once the nuclear threshold is crossed, the world enters territory unseen since 1945. As NATO officials have warned, “crossing the nuclear threshold would fundamentally change the nature of the war.” The post-World War II taboo on nukes would be shattered[51]. Even if Russia’s initial use was a one-off (say, a single low-yield bomb against a military target), the immediate question would be: what next?

Western leaders have made clear there would be serious consequences for any nuclear use[52]. However, they have deliberately kept ambiguity about what those consequences would be, to keep Russia guessing. Most experts believe NATO’s first response to a tactical nuke would be conventional – not nuclear – in order to punish Russia while trying to avoid all-out nuclear war. For example, NATO might respond by directly intervening with overwhelming conventional force: launching airstrikes to wipe out the Russian unit that used the nuke, or sinking the ship/submarine that launched it[53]. The U.S. could also lead massive cyber attacks or other non-nuclear measures to cripple Russia’s military. The aim would be to make Russia pay a heavy price, but without immediately firing nuclear weapons back, in hopes that the conflict could be contained at a lower level.

However, there is no guarantee that nuclear conflict could remain limited. If Russia felt further conventional punishment would threaten its forces or territory, it might respond with a second nuclear strike, perhaps a larger one. Each side would be under pressure to deter the other from escalating – which could perversely mean they themselves escalate. The U.S. and NATO might start taking steps like dispersing their nuclear-armed submarines and bombers or putting nuclear forces on higher alert, to show resolve. The fog of war and high tensions could lead to misinterpretation of these moves. In a worst-case cascade, tit-for-tat strikes could ensue. NATO has its own nuclear options if pushed – the United States could potentially use a proportional nuclear response, such as deploying a low-yield nuclear warhead (like the W76-2 on a submarine-launched missile) against a Russian military target[54]. The U.K. and France also have strategic nukes that would enter the equation. Once both sides start trading blows, the escalation ladder could rapidly climb toward strategic nuclear exchange, meaning city-busting bombs flying at Moscow, Washington, and beyond[55]. This is the nightmare scenario of global thermonuclear war – something leaders on all sides desperately want to avoid.

Russian doctrine actually acknowledges this risk; that’s why it emphasizes nuclear use only as a last resort. The concept of “de-escalating” a war with a nuke assumes the other side will hesitate to retaliate in kind. NATO likely would hesitate – but it would still retaliate in some form. The danger is that Russia’s attempt to force a resolution could instead open Pandora’s box. It’s worth noting that even during tense Cold War crises, the superpowers managed to step back from the brink. The hope is that, even if a Russia-NATO conflict reached a dire point, cooler heads would find a way to stop before the point of no return.

From Russia’s perspective, nuclear weapons are the ace card to prevent NATO from even getting to that dire point. By brandishing the threat, Putin hopes no one will ever test him to see if he’s bluffing. It’s a high-stakes mind game: appear ready to “go all the way” so that no one calls your bluff. But if the bluff is called – say, if NATO intervened directly in a war – Putin would face an excruciating decision. Using a nuclear weapon might be the only way for him to avoid a defeat, yet it would also make him the instigator of a potential global catastrophe. The current Russian philosophy is to make sure that decision never comes. That is why, for all the fiery rhetoric, Putin still maintains that Russia would only use nukes in defensive circumstances.

Russia’s Nuclear Posture Today: Deterrent or Danger?

In the end, Russia’s nuclear doctrine walks a fine line between deterrence and danger. On one hand, it serves Moscow’s interest to project strength and frighten its adversaries – hence the lower thresholds and frequent reminders of “we have nukes.” On the other hand, the Kremlin knows that actually unleashing nuclear weapons could spell disaster for Russia as well. The historical attitude, from Soviet times to now, acknowledges that nuclear war is not winnable in any traditional sense. As the Cold War saying went, “mutual destruction” would be the result. That logic still holds.

What has changed is Russia’s willingness to invoke nuclear threats as a political lever. The evolution of its doctrine reflects a state that feels cornered by NATO’s superior conventional might and by encroaching Western influence in its neighborhood. By widening the scenarios for nuclear use – now including conventional conflicts over territory – Putin is effectively saying: “If you back me into a wall, I might do the unthinkable.” It is a strategy of deterrence through uncertainty. The world has to take that threat seriously, even if it’s mostly posturing, because the stakes are existential.

For the general public, the notion of Russia firing nuclear weapons can be terrifying. It’s important to understand that, for all the aggressive doctrine, the use of nukes remains Moscow’s last resort. The Kremlin gains far more from nuclear weapons as a threat than as an actuality. The coming years will likely see continued nuclear rhetoric from Russia – announcements of new “super-weapons,” deployment of tactical nukes to places like Belarus, and bold doctrinal statements. These are aimed at dissuading the West from direct conflict. As of now, despite the war in Ukraine and high tensions, Russia has kept the nuclear genie in the bottle.

Could that change? Yes, if Putin’s regime truly felt its survival was on the line, all bets would be off. Short of that, the calculus of self-preservation kicks in: using a nuclear weapon is a roll of the dice that could lead to Russia’s own destruction. Thus, Russia’s nuclear doctrine – for all its menacing tone – is ultimately about preventing war, not provoking one. It is a shield of last resort, albeit one rattled loudly. How far could they go? In theory, all the way. In practice, Russia hopes it never has to go there, and so does the rest of the world. The precarious balance of nuclear deterrence, born in the Cold War, endures into the 21st century – with Russia’s policies at the unsettling forefront of that balance, walking the tightrope between flexing its atomic muscle and avoiding a fall into apocalypse.